Film studies has broadened the scope of writing about film and also broadened its readership, moving beyond the exclusive domain of film scholars and academics teaching film theory. Motivated by the need to express their passion for cinema, academics from different fields as well as non-academics are entering this field of specialist writing.

Somdatta Mandal, who retired as the chair of the English department at Viswa Bharati, Santi Niketan, is the author of Reflections, Refractions and Rejections: Three American Writers and the Celluloid World (2002) and Film and Fiction: Word to Image (2005). Her latest work comprises 18 powerful essays dealing with three quite different sections – Thematic Studies, Eminent Personalities and Directors, and Individual Films. Indeed, this book has enough material for three separate volumes. Although purely academic, Mandal avoids heavy theory that might confuse general readers, and her language and style are jargon-free.

Her socio-historical approach to cinema touches on themes such as partition films and its impact both in Punjab and Bengal, and in the representation of minority communities such as Anglo-Indians and Muslims. While this book provides a strong frame of reference for film studies students and scholars in these areas, it is a little surprising that the author has left out Shyam Benegal’s three Muslim-centric films – Mum (1994), Sardar Begum (1996) and Zubeida.

Interestingly, the book includes both well-known films that the reader may have seen many times, as well as some that are also less well-known, and includes discussions and analyzes that deliberately stray into sociological issues that shed light and raise questions. Among these one can mention her analysis and study of films like that of Deepa Mehta Earth 1947 based on the novel by Bapsi Sidhwa The Ice Candy Manand a very detailed analysis of Eisha Marjara’s little-known film Desperately searching for Helen in Chapter Aping the Vamp & Identity Issues in the Diaspora.

Mandal’s analysis of the ‘Partition’ films is very insightful. The event has become something of a double-edged sword for filmmakers, who often view it through cinematic lenses and personal perspectives. This section is divided into four detailed chapters. The first, Dismemberment and/or reconstitution: Visual representation of the partition of Bengal is the most important since most Indians associate partition with Punjab and Bengal is hardly discussed. The second, Reviving the Partition of Bengal in Documentary includes a detailed study of Supriyo Sen’s two-part recollections of Partition as seen by his parents in the films Returning home and Fantastic Homeland. The third section, Celluloid representations of the partition of Punjabscans movies like TamasML Anand’s Lahore (1949), considered one of the first attempts to portray the partition of India on celluloid, and Kartar Singh (1959) directed by Saifuddin Saif, which the author states is “considered one of the all-time great Punjabi films ever to come out of Pakistan”.

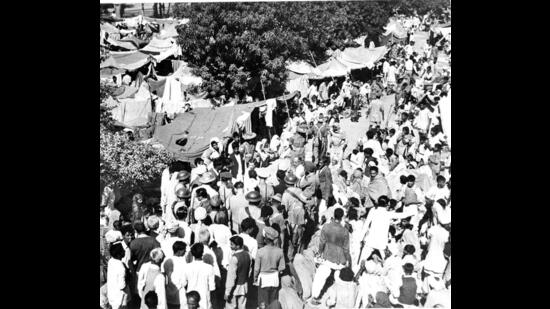

Among the mainstream Indian films, surprisingly the author mentions the films of Manmohan Desai Carpets (1960) which deals with the director’s favorite formula, but with the action set on the eve of Partition. And who can ever forget MS Sathyu’s classic Garm Hawa based on the story of Ismat Chughtai? The section titled Films about separation, borders and survivaldiscusses classic films such as Nemai Ghosh’s Chinnamul (1951) was shot almost entirely at Sealdah Station in Calcutta, filled with real refugees waiting – for what, they have no idea. Interestingly, a small role was played by a young man who approached Ghosh for work in his film. His name is Ritwik Ghatak.

Apart from the Ghatak trilogy based on the impact of Partition on the families and youth of Bengal, the author also takes a close look at some Bengali films made in the 1970s. Among them Bimal Basu Nabarag (1971) starring Uttam Kumar and Suchitra Sen, by Rajen Tarafdar Palanca (1976) and the first production from Bangladesh, Surya Dighal Bari (1976), co-directed by Masiruddin Shaker and Sheikh Niamat Ali.

In Women in film representation, Mandal takes us on a journey through film adaptations of Tagore’s stories and novels. Although questions such as ‘Was Tagore a feminist?’ have been explored and analyzed to death, bring out Mandal’s personal interpretation of female characters from Teenage Kanya through Harulata to GhareBaire.

An enlightening chapter, May you be the mother of a hundred sons! analyses Struggle against motherhood in Bengali cinema with an emphasis on Rabindranath Tagore’s childless women in his creative work but also on the Tagore family. This is a subject that few have dared to touch. Within the Tagore family, Debendranath Tagore’s son Jyotirindranath and grandson Balendranath (son of Birendranath) had no children. Three of Tagore’s children’s marriages were childless and his only son Rathintranath was also childless. Mandal also examines childless women in Satyajit Ray’s films (Monihara, Devi, Charulata and GhareBaire) along with some women in Rituparna Ghosh’s films like Hilarious and Andarmahal.

The book has a concise foreword by renowned film theorist, critic and scholar MK Raghavendra and a detailed introduction by the author herself. While the cover art is attractive, the photographic reproductions of film stills lack clarity as they are printed within the textual material rather than on separately printed and bound art paper.

In short, this is an insightful book that will appeal to both the film scholar and the intelligent general reader.

Shoma A Chatterji is a freelance journalist. He lives in Kolkata

The opinions expressed are personal

“Typical alcohol specialist. Music evangelist. Total travel scholar. Internet buff. Passionate entrepreneur.”